On April 7, 2016, the Allard Prize and the Liu Institute for Global Issues welcomed Greg Constantine, a self-taught documentary photographer from the United States. Constantine presented his 10-year project and book, Nowhere People, which documents the plight of stateless communities around the world.

Having visited eighteen different countries, Constantine knows from experience that, “Statelessness is not an issue that is isolated to little pockets…you can find it on every continent, in every kind of socioeconomy.” He observed, “Most stateless people that I have met…feel that they have been marginalized so much that their country, the place that they are from, and their neighbours really don’t even know that they exist or recognize that they belong to the world.”

Constantine’s photograph named “Boys and men carrying mud in open space” was selected as a winning entry of the November 2014 cycle of the Allard Prize Photography Competition. The photograph depicts a 7 year-old Rohingya child who is hauling mud at a work site near one of the internally displaced persons (“IDP”) camps. The mud was used to construct a man-made dam and pond so displaced Rohingya can catch fish and sell them to other camps. The child depicted does not go to school and is paid less than $1 a day.

In 2005, Constantine witnessed 300,000 Biharis from the Urdu-speaking community in Bangladesh who had been stateless up until 2008. The Bihari had been confined to isolated ghettos in urban centres where they received no government assistance, education or medical care, and were unable to gain legal employment. In this context, Constantine highlighted the power of youth in these communities. “The youth…in my experience, are the ones who are actually really making change. They…are the driving force.” In 2008, Urdu-speaking Bihari youth took their case to court, which resulted in the Bangladeshi government extending nationality to the entire community. Unfortunately, this is one of the rare stories of success for stateless communities.

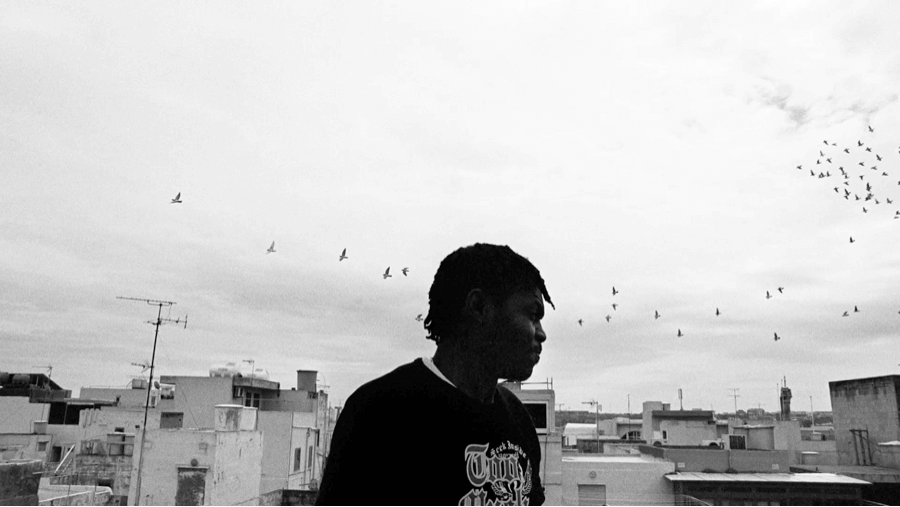

Constantine discussed several other individuals, including Ibrahim, who was born in Sierra Leone without documents. Ibrahim had been displaced by war twice before getting on a boat to travel from Libya to Italy. In 2011, his boat was intercepted in Malta, where he then spent two years in detention and was rejected twice for asylum. Now, he is stranded in Malta with nowhere to go.

Ibrahim said to Constantine, “Where is my home? I don’t know…I see people moving, going up, and coming. People travelling. I saw the plane flying everyday…People are going from country to country, which I never had the access to do. So, for me, it’s like my whole life has been stopped.”

A University of British Columbia graduate asked Constantine how he was able to gain the trust of the people in stateless communities. He credited his success to both his translators and his ability to spend significant time with communities.

An audience member from Kenya asked Constantine about the reactions he received during his exhibitions in Kenyan communities. Constantine described how he was given a grant to work with Nubian youth to collect, digitize, archive and curate old, black and white photographs that Nubians kept in shoeboxes—some dating back to 1908. These old photographs showed a proud, privileged community, which he juxtaposed against his recent photographs, years after Nubians were stripped of their citizenship, displaying a lost community. This juxtaposition confirmed to young Nubians that the proud histories they heard about from relatives were true and mobilized the youth to continue the struggle to be recognized as citizens.

When asked about the progress of efforts to eradicate statelessness, Constantine pointed out that in 2005 there were only a few organizations dedicated to statelessness, such as the Open Society Foundations and the UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees). Over the past few years, however, he has seen more organizations recognizing statelessness as an important human rights issue, including domestic organizations, which are contesting citizenship laws internally. Now, there are also regional federations working in solidarity on statelessness, such as the European Network on Statelessness and the Americas Network on Nationality and Statelessness. The UNHCR recently launched the #IBELONG campaign aiming to eradicate statelessness over the next 10 years.

The event concluded with lively discussions amongst participants, a book signing, and a reception.

To purchase Nowhere People, please click here.