Abdalle Ahmed Mumin

Abdalle Ahmed Mumin A prominent Somali journalist and human rights activist, Mumin cofounded the Somali Journalists Syndicate (SJS), an organization instrumental in advocating for press freedom, providing support to journalists facing threats, and challenging oppressive governmental directives aimed at censoring the media. Mumin’s dedication to journalism and human rights has subjected him to displacement, torture, and persecution, yet he remains committed to advocating for human rights and press freedom in Somalia through the relentless pursuit of truth.

Andréa Ngombet

Andréa Ngombet A Congolese civil society leader, political activist, and expert on kleptocracy, Ngombet is dedicated to promoting democracy and combating corruption in the Republic of Congo. He is the founder of the Sassoufit Collective, an organization advocating for democracy and the rule of law in the Congo Brazzaville. His work has come at profound costs, yet he continues to fight against corruption and kleptocracy, despite a dictatorship regime that imposes silence.

Virginia Laparra

Virginia Laparra Laparra, the former head of the Special Prosecutor’s Office Against Impunity (FECI) in Guatemala, fought against the corrupt justice system in Guatemala. She faced criminal proceedings for her work, which resulted in her spending 680 days in Guatemala’s maximum-security prison and then under house arrest. Despite these hardships, she refused to back down or compromise her integrity. Her arrest and subsequent detention have been widely criticized by human rights.

Abdalle Ahmed Mumin

Abdalle Ahmed Mumin A prominent Somali journalist and human rights activist, Mumin cofounded the Somali Journalists Syndicate (SJS), an organization instrumental in advocating for press freedom, providing support to journalists facing threats, and challenging oppressive governmental directives aimed at censoring the media. Mumin’s dedication to journalism and human rights has subjected him to displacement, torture, and persecution, yet he remains committed to advocating for human rights and press freedom in Somalia through the relentless pursuit of truth.

International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ)

The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) is an independent global network of 280 journalists across more than 100 countries. In addition to running their own independent newsroom, ICIJ has directed the largest cross-border collaborations in history, convincing reporters across the globe to set aside traditional rivalries to uncover corruption, abuses of power and grave harms inflicted on the world’s most vulnerable people. ICIJ has introduced innovative developments to journalistic infrastructure that have allowed hundreds of journalists to jointly gather, share, and investigate millions of documents to expose broken systems and widespread wrongdoing. These innovations have facilitated many ground-breaking reports including the Panama Papers, the Pandora Papers, and the Luxembourg Leaks, among others. Their unique contributions have resulted in criminal investigations in numerous countries and invited greater scrutiny into the gaps and loopholes that allow systemic corruption to continue.

Pavla Holcová & Ismael Bojórquez Perea

Pavla Holcová work as a human rights defender and later as a journalist led her to uncover high-level corruption and criminality across the globe. In 2013, Holcová founded the Czech Centre for Investigative Journalism, an independent news outlet that contributes to other journalism initiatives, including the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP). Together with her colleagues, Holcová has contributed to many ground-breaking investigations, including the Azerbaijani Laundromat and the Paradise Papers. Her work uncovering these criminal networks made her and her colleagues targets for smear campaigns, harassment, and violence. In 2018, Holcová’s colleague, Ján Kuciak, was murdered along with his fiancé while investigating a new story on corrupt dealings between the Slovak government and organized crime entities. Instead of silencing her, Jan’s death renewed Pavla’s resolve, and she carried on with his investigation, determined to publish the story and demand justice for Jan. The investigation contributed to the fall of the Slovak government and led to several criminal investigations and charges.

International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG)

The International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG) was created in 2007 in a joint agreement between the United Nations and the Guatemalan government. The Commission was designed to strengthen and support Guatemala’s judicial institutions and to investigate and prosecute corrupt actors and criminal groups that had infiltrated state institutions following Guatemala’s decades-long civil war. CICIG led over 120 cases and exposed more than 70 criminal networks, revealing the true extent of corruption and criminal activity in the country. The Commission’s efforts led to the removal of more than a dozen corrupt judges and the expulsion of more than 1,700 officers from the National Civilian Police. CICIG also sought to create more just and transparent judicial institutions by promoting major legal reforms to improve Guatemala’s investigative and prosecutorial capacity and responsiveness. CICIG’s efforts reduced impunity rates for violent crimes and restored Guatemalan peoples’ trust in the justice system. A 2017 poll showed that 70% of Guatemalan people had confidence in CICIG, and the Attorney General’s Office had one of the highest levels of public trust for a local institution. CICIG ceased operations in 2019, after 12 years in the country. Then-President Jimmy Morales, who had been investigated for corruption, declared CICIG a threat to national security and unilaterally terminated the agreement.

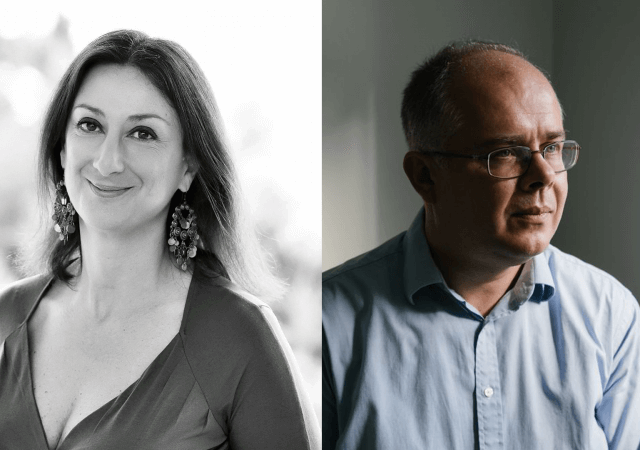

Daphne Caruana Galizia & Howard Wilkinson

Daphne Caruana Galizia Daphne Caruana Galizia worked as an investigative journalist, blogger, and anti-corruption activist for over 30 years. Daphne focused much of her investigative work on uncovering crime and corruption in Malta’s ruling class. She began her journalism career as a columnist in Maltese newspapers and worked for The Sunday Times of Malta and The Malta Independent, among other publications. In 2008, she started a blog, Running Commentary. The blog gained a large following and quickly became one of the most popular websites in Malta, regularly attracting more readers than the entire country’s newspapers combined. The nature of her reporting made her a target for abuse, slander, and intimidation by those she was exposing. She received near-daily threats and attacks intended to silence her; despite the barrage of violence and intimidation, Daphne continued her work. In 2016 following the release of the Panama Papers documents, Caruana Galizia uncovered that two high-ranking government officials were the beneficiaries of secret offshore accounts. She discovered that the officials were also due to receive payments from 17 Black Limited, another Panama shell company owned by businessman, Yorgen Fenech. On October 16, 2017, Daphne was killed after a bomb placed in her car detonated. Her death sparked protests around the country; demonstrators took to the streets to protest rampant corruption in Malta and to demand justice for Daphne’s death. The demonstrations triggered a political crisis resulting in the resignation of several government officials, including the Prime Minister. Four individuals – including Yorgen Fenech – have been charged in connection with her murder, but none have yet been convicted. Daphne’s family started the Daphne Caruana Galizia Foundation to continue her work and to support investigative journalists. “Receiving the Allard Prize for International Integrity on behalf of our mother, Daphne Caruana Galizia is both humbling and encouraging,” said Daphne’s family. “It not only recognises her work in exposing corruption and defending the public’s right to know, it also recognises that Daphne should be celebrated for everyone’s sake, because her example of courage, integrity and humour in the face of adversity are so badly needed today and will be for many years to come.” “The financial part of the award will be dedicated to the objectives of the Daphne Caruana Galizia Foundation: ensuring full justice for Daphne and the guardianship of her work; protecting investigative journalists and ending impunity for the murder of journalists; supporting independent, non-partisan media; and supporting public interest litigation and access to justice. We hope that the honour itself will inspire those who have taken up Daphne’s work to never give up and that it will encourage others to take up the fight against corruption and abuse of power.”

Azza Soliman

Over the past 25 years, Azza Soliman has dedicated her life to battling corruption and injustice faced by Egyptian women. The prominent women’s rights lawyer has fought for the inclusion of women in political, economic, and social activities, focusing on both the private sphere and the judicial system. As co-founder and current trustee of the Centre for Egyptian Women’s Legal Assistance (CEWLA), she has operated numerous campaigns to promote gender equality through legislative reform and raising awareness of women’s issues in Egypt. Azza has advocated for women since her politically active days in university, where she studied how fatwas contributed to perpetuating violence against women in Egyptian culture. Since then, she has worked extensively to implement training and legal-awareness programs on gender equality and conduct studies on subjects such as violence against women, honour crimes, marital rape, women’s right to divorce, and Egypt’s personal status laws. Because of her work, Azza has faced judicial harassment from an Egyptian government resistant to the missions of NGOs such as CEWLA. In 2015, Azza was unjustly charged with unauthorized protest and public order violations after testifying against a policeman whom she witnessed killing a female human rights defender during a protest. Continuing the Egyptian government’s crackdown on civil society, Azza’s private assets were frozen and she was arrested and interrogated about human rights NGO funding in December 2016. She was released on bail, but still faces ongoing government scrutiny as the public face of women’s rights in Egypt. As a PILnet (the Global Network for Public Interest Law) International Fellow, Azza is developing a project to expand access to legal services for marginalized communities in Egypt. She has also created the Religious Reform & Renewal Forum (RRRF) for social scientists, lawyers, politicians, and religious leaders to discuss relevant issues and causes related to women in Islam. To date, Azza has influenced a number of laws in Egypt, including providing rights for children born out of wedlock and including the mother’s name on all birth certificates. She was also the first to propose a civil law governing divorce, inheritance, and custody — among other rights for both Muslims and Christians — and the Nationality Law for Egyptian women married to non-Egyptians. A tireless advocate for women’s access to justice, Azza continues to serve some of the most economically and politically marginalized women involved in the Egyptian judicial system. What are your thoughts on being selected as a finalist for the Allard Prize? “Being nominated as a finalist for the Allard Prize makes me have a lot of gratitude as well as feel appreciated and motivated. I have been living under oppression in Egypt, which has specially intensified in the past three years. I feel that my nomination is a conformation that my work is acknowledged and needed. Moreover, it reminds me that there is spark of hope in this darkness. It also shows that more people are aware of the oppression that women human rights defenders (WHRDs) are facing in this part of the world. During the last three years, I received messages from many people telling me that I, Azza, am not alone in this fight. Having wide support makes me feel safer in this ugly, scary and tiring fight against an authoritarian regime, which sometimes changes its ways under international pressure. When I was arrested by the police last year, it was national and international pressure that helped me regain my freedom despite the fact that I was released on bail and that I am still among a list of of human rights defenders who risk receiving a life sentence in prison at any moment.” What inspires you to do the work that you do? “What is most inspiring in my work is when I’m able to help marginalised women regain their rights. To see their happiness when we succeed in empowering them and the impact of these victories, even the small ones, on their lives. I’m talking about basic rights: safety, freedom and equality. I see my work growing; the women I helped yesterday are helping other women today. We are speaking of survivors of different kinds of violence — whether domestic, political, social, cultural, religious or economic — [who help] other women survive. They give me hope, hope of a future which is more fair and just. I have a dream; to build an Egypt where there is rule of law. I dream of changing our culture and religious discourse to stop the oppression of women. Together with other resilient and brave women, we shall achieve this dream despite the hardships we are facing today.”

Car Wash Task Force (Força Tarefa da Lava Jato)

Beginning as a local money-laundering investigation in 2014, Operation Car Wash grew into the largest anti-corruption campaign in the history of Brazil and, perhaps, the world. The Car Wash Task Force has been responsible for billions of dollars in recovered bribes, and criminal charges against hundreds of political and corporate operatives, changing the nature of Brazilian politics and its culture of criminal impunity. The operation centered on a scandal surrounding Petrobras, Brazil’s state-run oil company. Prosecutors discovered that large construction and engineering firms paid more than $2 billion in bribes in exchange for lucrative contracts of Petrobras. The money was used to support a number of political campaigns that kept prominent officeholders in power and for their illicit enrichment. Over time, prosecutors and federal police uncovered a network of corruption that ran through the Brazilian Democratic Movement Party, the Progressive Party and the governing Workers’ Party, as well as a host of major corporations whose top-level officers were involved in the kickback scheme. More recently, investigations spread over many offices of the federal, state and municipal governments, involving hundreds of politicians of more than 25 political parties. Ultimately, federal police arrested a sitting Senator, six former Congressmen, a party Treasurer, and some of Brazil’s most powerful executives, bringing charges against 280 people and dispensing more than 1500 years worth of criminal sentences. Criminals and companies have agreed to give back more than $3 billion, in a country where no cent is recovered in criminal cases in general. In 2015, Marcelo Odebrecht, the CEO of Latin America’s largest construction company, Odebrecht S.A., was sentenced to 19 years in prison for his role in the scandal, and ultimately the company, in a joint resolution with another company, Braskem S.A., involved in the scheme, agreed to pay back more than $2 billion in a resolution led by the Task Force with help from authorities in Switzerland and the United States. This was the largest corruption penalty ever levied by global authorities. The Car Wash Task Force was awarded the Transparency International Anti-Corruption Prize in 2016. Having exposed the shady underbelly of Brazilian politics, success gave the team the firepower to push for legislation that would help public officials and law enforcement prevent, root out, and prosecute corruption in its public offices. By bringing to justice dozens of high-ranking officials and executives who many thought were untouchable, the Car Wash Task Force has brought about a new era of integrity and accountability in Brazil. What are your thoughts on being selected as a finalist for the Allard Prize? “I [Deltan M. Dallagnol] feel very much honored for being part of a huge team working on the Car Wash case. Because the struggle against corruption in Brazil goes much beyond the Task Force, I would like for each public servant and citizen who contributed to this case and to the cause to feel that this nomination is also recognizing her contribution. More than that, I want them to feel that they have the support of millions of citizens of the world, represented by the Allard Prize community, who are in solidarity with regards to the pain and suffering that corruption causes people everywhere. Finally, I also feel grateful to the Allard Prize, since the selection of the Task Force amongst the finalists renews our strength in this long-term battle.” What inspires you to do the work that you do? “Much more than punishing the persons who committed corruption, which is of course a matter of Justice, what inspires me is a humanitarian motivation. Behind the faces of corrupt public employees, politicians and businessmen, there are millions of Brazilian citizens, people of flesh and blood, who suffer the consequences of corruption. It is all about loving our people. I am talking about people who are dying in the lines of Health Care Institutions, waiting to be taken care of. Persons are injured everyday in accidents caused by road potholes. Young people do not have opportunities because the educational system was stolen. In Brazil, more than 35 million people do not have access to tap water and more than 100 million do not have access to the sewage system. All this drives me to do my best in my job and as a citizen to make a difference.”